Nov. 20, 2023

New UCalgary research underlines potential health threat from mosquitoes in northern climates

Picture the scariest animal that you can think of. Lion? Tiger? Bear? Mosquito?

Mosquito? Really? Mosquitoes often don't play a significant role in northerners' lives in our cold climate, aside from the itch of their bite. For most of the global population though, mosquitoes are a very different story — one of illness and death.

Soon enough, that could be the case here as well. Recently, invasive mosquitoes that carry West Nile virus have also been found in Alberta, so it may be high time that us northerners start thinking more about these little pests.

And UCalgary Faculty of Veterinary Medicine’s (UCVM) Dr. John Soghigian, PhD (Biology), couldn’t agree more. “Mosquitoes are among the deadliest animals on earth owing to the pathogens they transmit when blood-feeding, so their study is immensely important to human and veterinary health,” Soghigian explains.

Soghigian’s recently published paper, "Phylogenomics Reveals the History of Host Use in Mosquitoes" in Nature Communication explores how mosquitoes are related to each other. By using a phylogenetic approach, in which the genome of an organism is reconstructed, rather than the usual morphological approach which looks at structural differences such as size or shape, researchers can gain significantly more data, leading to more robust and accurate results.

“This previous reliance on analyzing their morphology has resulted in contentious and often confusing ways of classifying mosquitoes, and hindered us from really using their evolutionary history to understand aspects of their biology related to disease transmission,” says Soghigian.

Why does it matter how mosquitoes are related to each other?

“Mosquitoes that are more closely related to each other are a greater risk of disease transmission. There are more than 3,500 species of mosquitoes, and relatively few transmit pathogens to humans,” Soghigian explains.

“We can use the evolutionary relationships among mosquitoes to help us better understand when, where, and why mosquitoes might transmit disease, because often, mosquitoes can be vastly different from one another. Different mosquitoes use different larval habitats for their young, bite at different times of day, and even live at different times of year.”

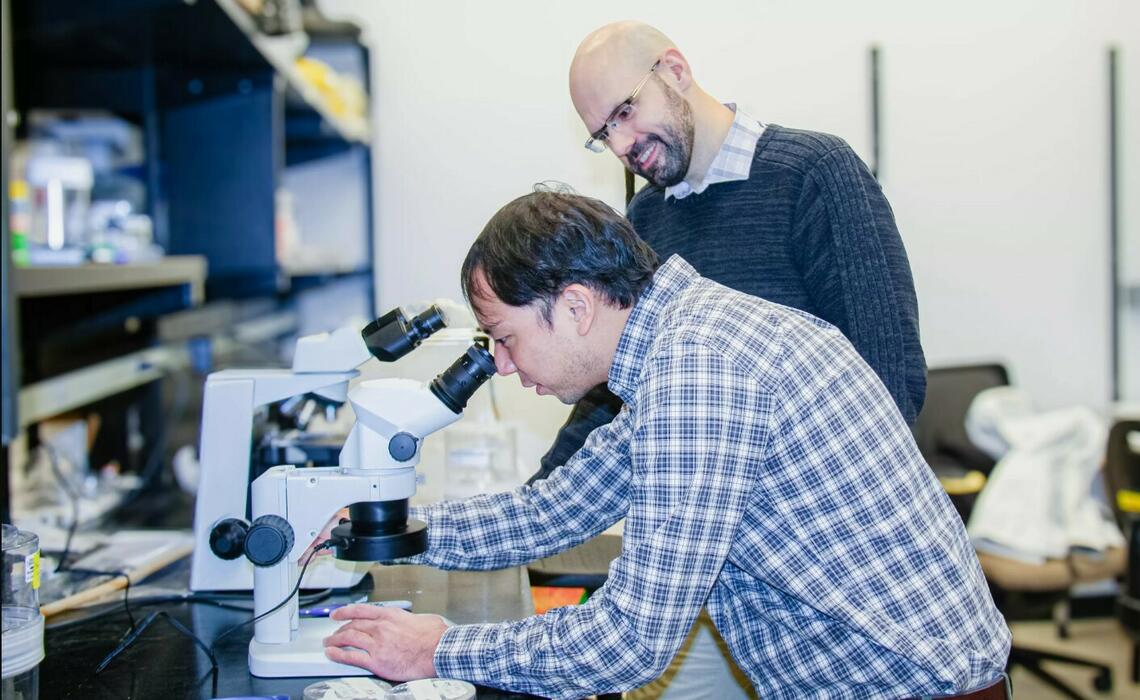

John Soghigian and Gen Morinaga inspect the morphological features of mosquito specimens.

Syed Rahil Tarique

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. “Many mosquito-borne diseases have no true cure, and while some vaccines are available, that isn’t the case for all pathogens mosquitoes transmit. So, quite often, we control mosquito-borne disease through combating mosquitoes themselves,” Soghigian points out.

Understanding their habits and preferences is often our only form of preventive action against their bites. Knowing when they are active advises us when to cover up or stay inside. Knowing where they lay eggs advises us of areas to avoid.

In the tangled web that is mosquito phylogeny, there are species that don’t bite at all, “instead eating other mosquitoes, or dancing with ants for food,” Soghigian says.

One of Soghigian’s favourite species, Toxorhynchites, offer us a look into a beautiful world that could be.

“Toxorhynchites are among the coolest mosquitoes. For one, they’re featured in Jurassic Park! And not to ruin the movie for you, but even if dinosaur DNA could be found in mosquito fossils, there’s no way it’d be in Toxorhynchites — that’s because these guys are just pollinators as adults.

“However, because they’re so different, it has been hard to understand how exactly they’re related to other mosquitoes. Our use of genomic data helped us out there. What’s cool about this is that there are only a handful of other mosquitoes that never bite at all — and almost all of those are in the group we found as ‘sister’ to Toxorhynchites!

“Could this mean there are some common aspects of the genetics of these mosquitoes that, through evolutionary time, can lead to mosquitoes that don’t bite?” Soghigian questions.

Alas, we are not living in a world with only Toxorhynchites, but also with the disease-carrying species. It’s these ones that have had big impacts on human history. For example, malaria-carrying mosquitoes have been around for a very long time, and in places with lots of malaria, people tend to have genetic traits that help protect them from the disease, like sickle cell trait.

Then there's our foe, Aedes aegypti. It's famous for spreading diseases like dengue and yellow fever today, but it caused big problems in the past. “In 1793, it caused a deadly yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia, and it was so bad that the U.S. Congress had to leave the city to stay safe,” Soghigian says. So not only have these disease-carrying mosquitoes left their mark on our genes, but also in our history.

Much like the flutter of wings in the butterfly effect, it can also be the sting of a simple mosquito bite that can have the most profound impact on our lives.